NEWS, EDITORIALS, REFERENCE

Introduction to Utilities

Alright. I don't want lose my cadence of approximately two posts a month. However, I've got a much needed summer vacation coming up in a few days which cuts this month short. I've got a couple of small news items to cover first.

Whoops, I didn't get this post finished before my vacation. So, this post didn't make it into July.

1) I recently got some more work done on C64 Luggable, and its documentation. The table of contents is now pretty much filled out, and I've published a new section, Front I/O. If you missed the announcement on Twitter and you're following along or interested in my progress on that project you can read about it here.

2) I have started to organize the C64 OS section of this site. It's mostly for technical documentation for programming, but it'll also include user documentation. I haven't written much content for it yet, but I've reorganized it so it is structured very similarly to the documentation for C64 Luggable. Sidebar table of contents, separate page for each section, with forum comments and analytics on each page. This will give me a place to start writing real documentation, that will be final for v1.0.

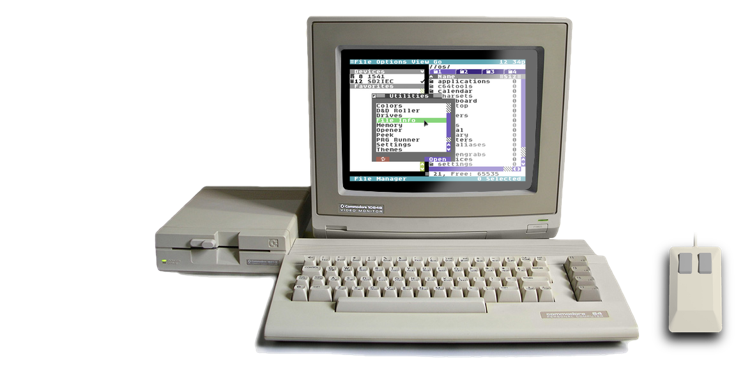

3) Speaking of v1.0. I'm still quite a ways off, many months I would guess. But I can see glimmerings of light at the end of the tunnel. For a long time, I was just coding and coding and I couldn't even run my code. It only worked in theory, even though a lot had been written. In this last few months things have really come together. The code is working, the system is running and I'm able to see and try out the fruits of my labor. If you've been following on Twitter, I've been able to bang out some utilities fairly quickly. And I've been doing the design work for several more. Finally being able to work on code that is not part of the KERNAL is a huge relief.

4) As if my attention isn't split enough ways already, I've also been putting some thought and time into packaging, and distribution of C64 OS v1.0. I've been doing some research on other OSes, (GEOS 1.0 and 2.0, Wheels, Risc OS, and early versions of Mac OS and Windows) to see what commonalities they have, and what applications and accessories they shipped with. I'm setting realistic targets for a core set of applications, utilities, and extras to include in C64 OS that I can A) actually accomplish, but that B) will make a compelling offering. Along with this, I've been writing the first draft of a User Manual. I'm formatting it for 5.5" x 8.5"1 and looking into reasonable production options. I've also decided to distribute C64 OS on 16 megabyte SD Cards, (sorry, not 1541! and not .D64) which will be affixed to the inside cover the User Manual. I'll have a lot more to say about this in future posts.

Now on to Utilities!

Desk Accessories

Back in the days of non-multitasking graphical operating systems, the idea of the desk accessory was invented to supplement the current application. I don't know if these were literally invented by Apple, rarely does anything come out of a void without any creative precursor, but they certainly were early. GEOS promptly ripped off the concept and even called them desk accessories.

The original Macintosh System 1.0, came with only a very few of them:

- Slider puzzle

- Scrapbook

- Key Caps

- Note Pad

- Alarm Clock, and

- a very basic Caculator

I believe the control panel was also implemented as a desk accessory. And that's it. GEOS had a similar set:

- Preference Manager

- Pad Color Manager

- Text Manager

- Photo Manager

- Note Pad

- Alarm Clock, and

- an equally basic Calculator

Very similar.

Thanks to Bo Zimmerman for the screenshot. More on zimmers.net here.

The idea is simple. The OS is not multitasking, so you can't run more than one program at a time. But, a little bit of something extra can go a long way towards making the system more useable without the expense and overhead of a full multitasking environment. If you run an application, like a word processor, paint program, or spreadsheet, without quiting out of the app entirely, saving the current document, losing your place and having to reopen everything afterwards, you can quickly pop open a desk accessory over top of the application. When the desk accessory quits, you're back to exactly the state you were in before, ready to keep working.

It was super handy to jot down a quick note, find a text scrap to paste in, set an alarm, or do a simple calculation. Mac OS was modeled metaphorically (and sort of still is) on the physical desktop. The desktop was a place where you could keep files, which looked like little pieces of paper. They could be put inside folders to organize them. There was (still is) a trash can, into which you can put the little pieces of paper you want to throw away, etc. GEOS ripped that concept off almost lock stock and barrel, including the trash and printer on the desktop, and the little dog-eared corners that you can click to flip through pages, like digital stationery.

Desk accessories, therefore, were an extension of that office/desktop metaphor. A desk accessory was like those little gadgets you have on your desk at work. A little note pad to jot down notes when someone calls. A calculator, an alarm clock. Eventually these OSes included card files and calendars, photo scrap books and more. These are all very metaphorically aligned.

Desk Accessories, meet Utilities

Mac OS was modeled on the office/desktop metaphor, because, at the time, computers were daunting technical contraptions that bearded unix wizards managed for banks, governments and the military. Home computers were simpler, but not markedly easier to use. Not only did the Mac introduce a mouse and graphical interaction like menus and icons, but also the metaphor was meant to make the parts of a computer more comprehensible to ordinary people. A file is like a piece of paper. A directory is like a paper folder. Scratching a file from a disk is like throwing the paper in the trash. It's easy. You already know how to use it. And it worked, many of those metaphors have stuck around for a long time. Normal, non-technical, people (like my mom) really are able to use computers.

Bearded Unix Wizards, Ken Thompson and Dennis Richie

The need for that degree of metaphor has waned though. First of all, the cultural impression of computers as advanced tools for uber-nerds is over. Everyone understands the utility of a computer. Everyone has a computer, or many computers: In their bag, under their TV, in their pocket, on their wrist or for a few, even in their eye glasses. Mass adoption of computers is no longer a marketing problem. And how to use them is also no longer a problem. The abstract concepts of a mouse-driven GUI, clicking, double clicking, dragging, right clicking, or of a touch screen, swiping, tapping, pressing, etc. have become baked into our mental lexicon without the need to augment them with a metaphorical link to physical objects.

For example, old Macintosh user manuals describe in painstaking detail exactly how a scroll bar works. It's like an old-fashioned scroll, from ancient Rome. The upper part of the content rolls up while the lower part unrolls, allowing you to smoothly move through content without turning pages. But who, today, thinks of a webpage as though it were structured like a papyrus scroll from antiquity? The point is, the metaphorical overlay has been lost, even though most of the interaction models have stuck around. And now they just make sense on their own merit, in no small part because modern children start using computers when they're two years old.

iOS is an example of an operating system whose interaction model was put together in the 2000s, rather than the 1970s/80s. Most of the desktop metaphor did not survive the transition. Likewise, C64 OS is not modeled on the desktop metaphor. It has a menubar, it has a mouse, and a graphical2 user interface. But it isn't designed to intentionally remind you of the familiar physical objects you'd find sitting at your office desk. Computers just don't have to do that anymore.

For this reason, gone is the name desk accessories.

In there place, we have utilities.

The lifting of limitations

I actually find the metaphor of the desk accessory to be quite limiting. There are very few things which actually fit well into that metaphor. On my desk is a stress ball, a dictionary, a coffee cup, a photo frame, a box of tissue, a bucket with pencils, pens, a ruler and a pair of scissors, and, Sticky notes. Some of these might translate, some of them not so much. Beyond that, the metaphor starts to become artificially constraining.

A utility, on the other hand, is something which is useful. And there are far more useful things that a computer can do than can be represented as an analog to some physical gadget on your desk at work.

And I don't think it's just a theoretical concern. Desk Accessories of yore really were quite constrained, and artificially so. Especially in GEOS.3 When a GEOS Desk Accessory is run, it takes over the computer completely, and doesn't allow for any interaction with the underlying application, in any way, other than seeing little bits of it that aren't occluded. But they're limited in other ways too: programmatically, they don't open each other, and applications don't open them. They don't exchange information with each other or with the application, (except via text and photo scraps written to disk) and while they are often used to record settings (the whole point of the Preference Manager, for example), they rarely if ever save state. The calendar forgets what month/year you were on, reverting to today, the next time you open it. The card file forgets which card you were last looking at. The text album forgets which page you were on. The notes forget which note you were looking at. And furthermore, you could only ever access a maximum of about 7 or 8 accessories. You had to use a third party accessory manager to rearrange the order of the accessories on the disk, in order to get access to a different set.

To be fair, on a C64, GEOS was running off very small, 170KB floppy disks with no folders. You weren't exactly going to have hundreds of desk accessories at your finger tips. So the menu only listing 7 or 8 was hardly the limiting factor. Also, it was hard for an app to be able to depend on loading a desk accessory programmatically, because, they couldn't rely on any of them actually being on the current disk. Usually the user would put the bare minimum on a work disk, to leave the maximum amount of room possible for content, like the pages of your geoWrite document.

98 1541 Floppy Disk Sides, fit in a single 16 MB Partition4

The world has changed. Even for C64 users, the world has changed, a lot. C64 OS requires a mass storage device that supports subdirectories. This might be a CMD FD, HD or RamLink, or it might be, preferably, one of the many SD2IEC devices, or alternatively an IDE64. The most constrained for storage of any of these is the CMD FD. You can do it, but, it's not recommended. The CMD HD and RL can have similarly small partitions created, but more realistically they'll have partitions in the megabytes, up to sixteen. 16 megabytes is equivalent to the capacity of 98(!) 1541 floppy disk sides. An IDE64 or an SD2IEC can have partitions with gigabytes, which, for all intents and purposes is an infinite, inexhaustibly huge expanse of storage. PC users might laugh at hearing me say that, but for an 8-bit computer, a 1 gigabyte SD Card will likely never be filled. But you're not limited to 1 gig, you could use 16 or 64 or 128 gigabyte cards.5

Where once, for GEOS, space was claustrophobically constrained, for C64 OS storage space can now be rounded up to infinity. That opens a lot of doors. Doors that aren't being taken advantage of by most C64 software.

Is it all just in the name?

My point in listing all of the limitations and constraints of desk accessories, both metaphorical and technical, is to provide a point of reference for utilities in C64 OS. They are—most emphatically—not just a change of name.

Some utilities will smell like desk accessories, because, hey, the desk accessories we're all familiar with are actually very useful. A calculator, a note pad, a scrapbook, a calendar. But, my plan is for there to be utilities that are unlike any desk accessory, and which applications depend on to fulfill critical functions. Let's go over some of those points raised above, and use them as talking points for comparison.

The original Macintosh desk accessories did not have all of the limitations of those in GEOS, but, the Mac also had more memory, higher capacity disks and a higher resolution screen. The discussion below, therefore, will be limited to GEOS, so that we're comparing C64s to C64s not Apples to C64s. (* play on words intended.)

• Taking over the computerDesk accessories take over the computer and prevent interaction with the application for as long as they are open. This limits the desk accessory to function as a stand-alone program that takes priority over the application.

Utilities in C64 OS can be opened and left open while the user continues to use the application. In my previous post, Command and Control, I gave the example of the Memory utility. You open it, put it off to the side of the screen and leave it open while using the application. It monitors memory usage and shows a visual map of allocations. The information is updated live. So as you use the application you can see it making new allocations and freeing up unused memory.

• Fixed position on screenDesk accessories have a fixed position on the screen. Once they open, they cannot be moved around. This causes them to cover over, or occlude in computer science terms, part of the application below. Some occlusion is unavoidable, obviously, but the inability to move the desk accessory means if part of the app is not visible but contains useful information, there is nothing you can do to see that information. Here's the canonical example:

Calculator, image from the original 1988 GEOS 2.0 User Manual, page 254

That image is from the GEOS 2.0 User Manual, which is conveniently available at archive.org. The usefulness of a calculator as a desk accessory is being demonstrated. A geoWrite document is open with some dollar figures. The calculator is open simultaneously, but it's sheer luck the calculator isn't covering the numbers below. If it were, there isn't a damn thing you could do about it. You'd have to close the calculator, then scroll the page some, and try again.

In C64 OS, the utilities can be moved. Be careful though, they should not be thought of as windows. The C64 OS KERNAL has no support for windowing. The utility has a screen layer, and it owns the whole layer. A utility doesn't have to be movable, its not completely automatic. However, I've abstracted out of the code a common include for drawing the utility's UI buffer to screen, which supports clipping at the left, right and bottom screen edges. This file can simply be included into the utility's source, and provides the code necessary to intercept mouse events, perform bounds checking, move the utility's UI by dragging its top bar, and re-orients the coordinates of events so the top left corner of the UI is at a virtual 0,0.

With very little effort by the programmer, utilities can be provided with the ability to be moved around. But the code to do this is not permenantly resident. It's assembled into each individual utility's binary.

I prefer to think of a utility, that can be moved via by its title bar, not as a window but as a palette.

Definition - What does Tool Palette mean?

A tool palette is a graphical user interface (GUI) element used to group together special functions in an application.[...] The tool palette groups together shortcuts to functions, usually in the form of icons or widgets. It is akin to the artist's palette used to hold and mix the different paint colors needed to create a painting.

A tool palette is also known simply as a palette. Tool Palette — technopedia.com

Palettes are like mini windows, that contain or group together tools that are meant to be used to operate on the application's data. More on this later.

• App does not actively refresh its appearence while belowThis is likely related to the point above. My guess is that the main reason desk accessories have a fixed place on screen is because there is no facility in GEOS to recomposite multiple layers. Before something overwrites part of an application's screen, the system itself makes a one-time, static, backup of the screen. Then it draws stuff over top of the screen. And when it's finished, it restores dirtied regions of the screen from the static backup.

This is how menus work in GEOS, for example. You click to open a menu. Before it shows that menu it copies the screen to a backup buffer. Then it draws the menu in place, overwriting the application's pixels in main bitmap memory. While the menu is open, the application is unable to update its appearance. When the menu is closed, the system takes the dimensions and coordinates of the menu, and restores ONLY those cells from the bitmap backup into the real bitmap screen, then it returns control to the application and the application is none-the-wiser.

Applications in GEOS are never required to be able to redraw their entire screen from scratch upon request. They are always allowed to assume that the screen looks exactly as they last left it. This puts the onus on the KERNAL to back up and restore the screen before and after anything disrupts it. I assume desk accessories draw very much the way menus do. While the calculator, for example, is open, the app cannot update its appearance, and cannot receive events. The bits of the screen around the calculator are a shadow of what the app had been displaying at the time the calculator opened. When the calculator closes, the KERNAL restores the screen under the calculator from the backup, and gives control back to the application, effectively unfreezing it.

From the very beginning C64 OS was designed with a multi-layer screen compositing system. Applications, utilities, and even system code that draws (such as the menu bar with the clock, or status bar) should never assume that the screen is how they left it. They must always maintain the ability to redraw everything, either from scratch, or from a privately maintained buffer, at any moment. This might have been too much to ask, of memory and processing power, for a fully bitmapped system. But for a text-mode UI, it's easily doable. And, it opens many doors.

Because the application is always required to be able to redraw itself, which it does when the menus are opened and closed, it can just as easily do that as a utility covers over part of it. This is what allows a utility to be dragged across the screen. As the utility moves, with each step the application redraws itself, and the utility redraws itself in a new position over top of that.

It looks cool to see animations happening beneath opened menus, but maybe it seems like a bit of a novelty. It is not a novelty that the application can redraw itself below an open utility, however. Imagine an IRC chat client, with messages coming in. You can open a utility that sits above the conversation, and continue to watch the conversation scroll by as you're interacting with the utility. You can even send an IRC message yourself without closing the utility. Utilities in C64 OS are much closer to multitasking than desk accessories ever were in GEOS.

• Cannot open another desk accessoryDesk accessories were never designed to link from one to the next. Real accessories on your desk don't really link together much either, so maybe it was metaphorically sound. For example, you couldn't start from the notepad and open the card file with the current note pushed into the note field of a new contact (to pluck a contrived example out of the air.) There was no way, from a desk accessory that handled one type of data, to directly open another desk accessory that was better suited to handle some portion of that data.

In C64 OS, utilities are being designed to be able to do exactly that. I'll give you a simple example. I've recently written two utilities: Memory and Peek, shown here.

There is a clear relationship between the two ideas, though they're meant for different purposes and they have different UIs. While it is possible to roll them both together into one utility, to do so would miss the point. Instead, imagine you double click the available memory section of the status bar, that opens the Memory utility so you can see more detail, and a visual map of memory allocations. Next, let's say you see a random page of allocated memory in the middle of the map, and you wonder who's holding on to that and what's in there. You can double click on that spot in the map and it will close the Memory utility (because there can only be one open at a time), and load in the Peek utility, and direct it to the page you clicked on. You can then inspect the contents of that particular spot in memory.

• Do not exchange messages or data with each otherObviously, if one desk accessory never opens another, there isn't much point in their ability to pass data to one another. But in C64 OS, they are designed to do that.

At the time of writing, though this may change, there is a byte in workspace memory that is used to hold a page number of data owned by utility space, but not by any particular utility. This allows a page of data to persist across the closing and loading of two utilities. Take the example of the Memory utility passing a memory page number to the Peek utility. The sending utility needs to know the expected data format of the receiving utility. Let's see how this would work.

Memory utility is open. The user double clicks a page in the map. Memory utility calls pgalloc to get a page of memory to use as a message buffer. Memory writes the page address into the workspace address dedicated for message passing between utilities. The Peek utility is known to accept a single byte message as the page it should open to by default. (Ignoring its previously saved state.) Memory thus writes the page number that was double clicked as the first byte of the allocated message buffer. Memory makes a system call to open Peek. This causes the system to initiate the process of properly quiting Memory, and then load Peek. When Peek initializes, it checks the workspace variable to see if it's non-zero. If it's not zero, then a message buffer page is allocated. It reads the first byte out of the message buffer, that's its own message format, and uses that byte as the default page to load. Then it deallocates the message buffer and sets the workspace variable back to NULL.

The process may change. To transfer just one byte, it's a bit of overkill to allocate a full page. And for some utilities one page might not be enough. But the general idea is that it's the responsibility of the sending utility to allocate the space and format the message in the expected format of the receiving utility. It's the responsibility of the receiving utility to check to see if there is a message, and to deallocate the space after it's received the message.

• Cannot be opened programmatically by an applicationActually, I'm not sure about this. It may be possible for a GEOS application to make a system call to open a desk accessory by name. However, the practical issue that they cannot be relied upon to be available on disk, meant no app in practice ever relied on a desk accessory to implement part of its essential functionality.

In C64 OS, utilities are intended to be able to implement the extended functionality of the application itself. These ideas are not new, of course. macOS has a standard color picker that is built-in. Any application can open the color picker, and it's the same across every application. Sometimes the underlying app has a color sensitive element in focus, sometimes it doesn't. When it does, any color chosen in the color picker is routed to that element to change its color. When it doesn't, changes to the color picker panel just go into the ether.

The very first utility I created for C64 OS was a color picker, shown above. I don't want anyone who writes an application for C64 OS to ever have to write a color picker UI. Instead, you should rely on the fact that a color picker is built into the system. An application can programmatically open the standard color picker utility, by name, whenever it needs the user to pick a color. Third party color pickers can be written to replace the default color picker, of course. Just give the alternative the same name and put it in the Utilities folder. As long as it provides the same core functionality, the applications that call it and receive data from it will never know the difference.

This takes us directly into the next point.

• Do not exchange data with the applicationWith the exception of via text and photo scraps, GEOS desk accessories don't exchange data with the application. In the example of our color picker utility, the whole point of it is to send a message to the application.

The application's main dispatch table has a vector to a message command (msgcmd) routine. This was formerly known as menu command (mnucmd). It is a vector through which different systems pass structured messages to the running application. The .A register holds the command type, and the use of the other registers vary depending on the command. Formerly, the menu system would call this routine and pass a menu item's action code to the application. Now, the menu system does the same thing, but it also passes the command type menu action code (0) through this vector.

This gives up to 256 different possible command types. One of which is claimed by the color picker. Now, it isn't just the one color picker utility that uses that command. ANY color-oriented utility that wishes to send a picked-color command to the application can use this command type. If the application doesn't interpret that command, or isn't in a state that is ready to receive a color, it just ignores it.

Other command types that will be send via utilities include: file open, file save, status request, external text paste, etc. Let's quickly take file save as an example.

- The file open and save dialog boxes are implemented as a utility. (I'm going to do them as one utility because there is huge overlap in their functionality).

- The user clicks file > save as… from the menu system.

- A menu action code is sent to the application.

- The application puts some message data into an allocated message block indicating "save" mode, and opens the file utility.

- The file utility opens, configures itself for save mode and deallocates the message block.

- It reads its state (discussed next) to figure out the default folder it should go to.

- The user potentially moves through the file system away from the current location.

- The user enters a new filename.

- When the user clicks the save button, the utility configures a fileref for the current location and entered filename.

- The File utility calls the application's message command routine with a "File Save" command type, with X/Y pointed to the new fileref.

- The application then saves its data using the fileref provided by the File utility.

- The application deallocates any previous fileref that was pointed to by opnfileref, and updates opnfileref to point to the new fileref. (Thus changing its internal reference to what file it has open.)

When the File utility is finished, I'll have a post that goes into much more detail about how it works and how it interacts with the application. But the point is, utilities exchange data with applications. When the application is opening a uiltity, it can allocate and configure a message block the same way two utilities pass messages to each other. A utility can use the message command vector to send messages to the current application, the same way the menu system passes action codes to the application.

• Do not save stateGEOS desk accessories sometimes write data to disk. For example, Preference Manager writes to the system's preferences file. Text Manager stores text in a text album. Note Pad writes its notes to disk. The calendar writes its events to disk, etc. But those are data that are managed by that accessory. Rarely (ever?) did a desk accessory write its state to disk.

State is different from data. If you have a note pad, the contents of the notes are the data. State is everything else, such as, where the note pad is positioned on screen, which note is currently open, how far into the note is the view scrolled, where is the cursor last positioned for editing, how big is the window (if resizing is supported.) For the C64 OS Memory utility, for example, where the utility is positioned on screen, which status message (total, fixed, used, or available) is selected, the refresh rate fast or slow, these are its state.

There is no KERNAL level support for saving and restoring a utility's state. However, the same common include that is used to support moving a uility by dragging its title bar, also includes code for saving and restoring a block of configuration data. A structured block of contiguous bytes, with default values, is coded into the utility somewhere shortly following its dispatch table. When the utility is initialized, it uses the utility's identity (every utility has to be able to identify itself with a short string, usually based on its name), to check for the presense of a config file inside the app bundle of the currently running app. If it finds such a file, it reads in from it a number of bytes specified by a constant, and overwrites the block of default config variables.

During the utility's quit phase, its block of config variables is automatically written to a file named based on its identity, to the current application's app bundle. The position of the utility on screen can be included in the block of config variables.

What this means is that the state of a utility is automatically stored and restored, on a per app basis. For many utilities this is ideal. For example, when you open the file utility, to pick a file, when the file utility closes, its current location (device, partition, path) gets saved automatically for this application. The next time you try to open a file again, for this application, the file utility returns automatically to the last used location. This is VERY convenient. And because it's on an app by app basis, in a different app, when you try to open a file, that instance of the file picker utility will default to the last used location for that app.

There may be certain types of utilities that would prefer to have their state global to all applications. A constant can be set to force that utility to read and write its state from a file in the system folder instead.

Hopefully you can begin to appreciate why it is that C64 OS requires a device that supports subdirectories. The fileref structure and the system's ability to know the path to the current application's bundle directory enable the system to automatically take advantage of directories to find resources, and store config data on a per app basis.

One more reason to use one of these, instead of one of these:

• User can only access ~8 Desk Accessories

Most GEOS applications have a GEOS menu in the top left corner (although, this is not necessarily the case, some applications don't follow this pattern.) In that menu can be found a list of Desk Accessories. The problem is that it only ever lists a maximum of about 8. To decide which 8 it reads through the disk directory, sorted according to how the entries are stored in the blocks on the disk. The first 8 it encounters are put into the menu in that order.

This has the nice benefit of allowing you to use the file system (the GEOS deskTop UI) to rearrange the icons on disk to create the order in the menu. The downside is, you only ever have access to 8 accessories. There are work arounds, but they're slow and cumbersome. For example, there is a desk accessory for managing desk accessories. You load it first, and it reads through the disk and lists the others. I think you can use it to rearrange them on disk to get access to a different set.

C64 OS also has a system menu, although I'm still working on this. It will, similiarly, list a set of Utilities. There are numerous differences though. How many can be in this list is only limited by how many menu items can be shown in a menu. If the status bar is hidden, that's 24 items. 24 is a lot more than 8.

Additionally, of course, this is not the only way to open a utility. Double clicking on various system elements, the clock, the available memory in the status bar, perhaps the disk status, can be used to open utilities, these don't need to be in that list of 24, so now we're up to 27. Plus, some utilities link to others, so those can reasonably be omitted from the list of 24. And, of course, applications can programmatically open utilities. So the open and save file dialogs, the color picker, date picker and others don't need to be manually accessible from the system menu.

Despite the larger accessible number of Utilities in C64 OS, I also plan to write a utility for managing which utilities appear in the system menu. Rather than rearranging files on disk, though, (because this can be tricky to do across different file systems, such as a FAT16 formatted SD Card, or the custom IDE64 file system), instead the menu will be built from a simple text file that is saved in the system folder. The text file lists the names of Utilities, one per line.

C64 OS's Utility loader loads them by name, so only a name is necessary, which double as the menu item labels.

The utility loads in a list of Utility names from the System's Utilities folder. It displays a scrollable list of them, with checkboxes to the left side. It also loads in the contents of the utilities.i file in the system folder. Any item that appears in utilities.i is drawn with its checkbox checked, all others with their checkbox unchecked.

The user can change which utilities are checked. When the user clicks the save button, a new utilities.i file is written from this list of checked options in memory. A system call is used to build the system menu from utilities.i. This is called automatically as this utility is quit, so the new selections are immediately reflected in the system menu. I'll try to get sorting into the first version of the organizer utility. But if not, one can always manually edit the utilities.i file. In fact, as can be done in Unix or early versions of Windows, the ability to manually change text-based config files is a big design goal in C64 OS.

One final point. The menu bar in GEOS is not reliably consistent. The date and time, for example, only appear on the deskTop. Inside an app like geoWrite or geoPaint, the clock disappears. Similarly, the contents of the other menus depends heavily on the whim of the app. Many third party GEOS applications do not include the GEOS menu. This makes me feel that geoWrite, geoPaint, geoCalc, etc., each build the GEOS menu manually.

In C64 OS, the menu bar is much more under the control of the system. It is a system feature. The system menu, with customized list of Utilities will be much more consistent from application to application.

Technicals… for another article

I'm already a week behind schedule on this post. And it's already over 7000 words long. Therefore I will hold off on the programming and technical details of Utilities for another post. Look forward to it later in August!

- 5.5" x 8.5" is a North American paper size standard. It's very close to A5, aka FREEZE64 fanzine size. It's standard Letter, folded in half. [↩]

- It's not rendered to a bitmap, but the interaction model is the same. You point and click to trigger behaviors. And sprites and custom characters do allow some graphical flourishes, thus I will continue to refer to it as a GUI. [↩]

- The Macintosh had more resources, it could run more than one desk accessory at a time, and you could switch between them. But if they were running, you couldn't interact with the application below. You can actually try this out here. [↩]

- Now you know why I'm planning to ship C64 OS on a 16MB SD Card, and not a 1541 disk, or even 2 or 3 or 4. A 16MB SD Card can be purchased in bulk for 50¢ a piece, and have the storage capacity of 98(!) 1541 Floppies. Plus, because they support subdirectories, they can be used as the boot volume. No need to install the software onto a larger medium. [↩]

- The uIEC was tested by Jim Brain with 128 GB cards, and it works with some, though not all of them. [↩]

Do you like what you see?

You've just read one of my high-quality, long-form, weblog posts, for free! First, thank you for your interest, it makes producing this content feel worthwhile. I love to hear your input and feedback in the forums below. And I do my best to answer every question.

I'm creating C64 OS and documenting my progress along the way, to give something to you and contribute to the Commodore community. Please consider purchasing one of the items I am currently offering or making a small donation, to help me continue to bring you updates, in-depth technical discussions and programming reference. Your generous support is greatly appreciated.

Greg Naçu — C64OS.com